In Montana, lack of mental health resources linked to growing gun violence, especially in hospitals

It’s hard to ignore the near-daily headlines about gun violence, overdoses, and crime, especially since many Montana residents remember that the state was once a much more peaceful place. The articles are widely read as locals can’t seem to take their eyes off the frequent violence that creeps closer to people’s backyards.

Many medical professionals have pointed to the severe lack of mental health resources in the state as one of the drivers for the increase in community violence. However, everyone is careful to point out that mental illness is not synonymous with violence.

Overall, violence is rare among people with mental disorders. But when mental illness goes untreated and is linked to other co-occurring issues like substance use disorders, environmental factors, or child abuse and neglect, risk factors for violent behavior can peak.

Three Montana murder-suicides in one week, including two in just over 24 hours, were particularly telling for Community Crisis Center director Marcee Nearly.

People also read…

“It’s clear that (people) aren’t getting the treatment they need,” Nearly said.

When mental illness is managed with professional help, most people can lead normal lives, but when left untreated, symptoms sometimes peak in hospital emergency departments.

Employees at Billings Clinic and St. Vincent Healthcare have noticed an increase in patients seeking treatment while in the midst of a mental health crisis. These patients tend to contribute more significantly to the increase in violence in hospitals.

A national survey found that 42% of emergency department attackers were psychiatric patients and 40% involved patients seeking drugs or under the influence of drugs or alcohol, according to the American College of Emergency Physicians.

But of the 163,000 Montanese diagnosed with a mental health condition and 44,000 citizens with serious mental illness, at least 47,000 people did not receive the mental health care they needed in 2020. Of those 48.6% did not receive care due to cost, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“The number (of assaults) has increased as substance use disorders (have changed), as different drugs have entered our community, as our communities have grown, but the resources have diminished” said Brad Von Bergen, Billings Clinic ED manager. “There’s a lot more financial pressure on people these days and people are dealing with alcohol, they’re dealing with drugs.”

Von Bergen worked as a registered nurse at the clinic for 30 years and noticed more mental health crises happening in the ER than ever before.

Billings Clinic emergency department manager Brad Von Bergen sits in a hospital bed in the surge unit in a hospital hallway in this October file photo. The hallway surge unit is used when the emergency department lacks traditional spaces to accommodate patients.

RYAN BERRY, Billings Gazette

emergency departurecomments

The Oct. 16 shooting at the Billings Clinic emergency department was a stark reminder of the scale of the mental health crisis plaguing Montana. During the incident, a suicidal patient suffered two gunshot wounds, one self-inflicted and the other by a responding police officer.

The management of the Billings Clinic emergency department said the increase in gun violence in Billings may be linked to the lack of mental health resources statewide.

“The resources available to people outside of the Billings Clinic have (decreased),” Von Bergen said. “It made it really difficult for our community when they needed help or had that place to go and now they don’t.”

When these people are in crisis, some end up at the Community Crisis Centre. If there is an overflow, people end up in emergency departments, Von Bergen said.

The clinic’s emergency director, Dr Jaimee Belsky, said people should always go to the emergency room if they are in crisis, but pointed to the lack of mental health resources in the community as the reason for the overflow of psychiatric units and long waits for the state psychiatric hospital. .

Billings Clinic emergency room medical director Jamiee Belsky shows off her emergency tag which alerts the clinic’s internal security team in the event of an emergency. Staff are equipped with these beacons and they were used the night of the ER shooting.

AMY LYNN NELSON, Billings Gazette

Referring patients to specialist psychiatric care is where dealing with mental health crises in the emergency room gets tricky.

When there are no beds available, patients end up boarding the emergency room, which isn’t very comfortable for an extended stay, Blesky said.

“It’s also just the nurses and what they’re trained to do. Our nurses are still trying to (treat patients in the emergency room), but at the same time they also have to monitor that patient at the same time,” Belsky said.

Counselors can spend one-on-one time with patients in the emergency room, but patients don’t have access to the group therapies that are often an integral part of treatment.

With more mental health care providers, more group therapy sessions, and more support services available, people may be seeking treatment for mental illness.

“Building (community) resources would give us more tools,” Blesky said. “I think that would help tremendously because they will redirect care immediately. So we’re not going to have as many acute attacks, but they’re also going to help you get out of (crisis care). »

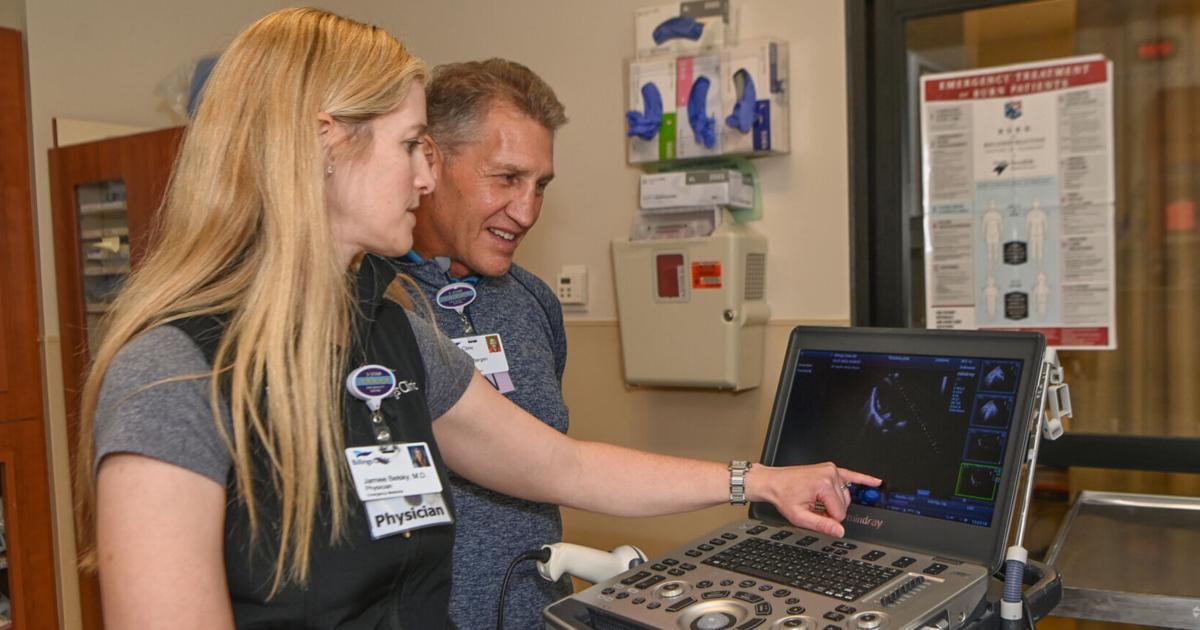

Billings Clinic Emergency Department Medical Director Jamiee Belsky and Emergency Department Director Brad Von Bergen work in their department on Friday, October 28.

AMY LYNN NELSON, Billings Gazette

The reduction in the State budget harms the treatment

Making an appointment with a mental health provider is becoming increasingly difficult in Montana. Therapists are full for months and waiting lists sometimes stretch beyond six months.

Community resources in rural areas in particular have evaporated at an alarming rate, according to Mary Windecker, executive director of the Behavioral Health Alliance of Montana.

The 2017 state budget cuts to the Department of Health and Human Services were largely responsible for the ensuing mental health crisis, Windecker said.

Prior to the $49 million budget cut, Montanans had access to social workers in their community who helped them stay on top of medications and access therapy to manage symptoms of mental illness or alcohol-related disorder. substance use (SUD). These resources allowed people to live relatively normal lives, Windecker said.

After budget cuts, social workers and providers were laid off en masse, and state mental health centers could no longer afford the same staff.

So when the pandemic hit, resources were already dwindling. People in Montana have faced blockages, isolation, loss and fear, and the mental health crisis has grown.

Now, historical discrepancies in Medicaid reimbursement rates have had a negative impact on behavioral health in almost every medical sector.

It is even more difficult to meet the demand now that accepting Medicaid comes with a significant financial loss. Facilities have limited the number of staffed vendors to keep doors open, Windecker said.

Professionals have summed up the situation as a mental health crisis that is, in some ways, unique to Montana.

This year alone, Billings was ranked as the most depressed town in the country. Thirty-one percent of residents have been diagnosed with depression by a professional, according to data from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

And due to widespread cultural stigma, Windecker expects there are countless people living with an undiagnosed mental health condition, though it’s hard to estimate without data.

But the data on those diagnosed are well documented.

In February 2021, about 35% of adults in Montana reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, but about 18% were unable to access counseling or therapy services, according to data from the Montana Chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

In Montana, 44,000 adults suffer from serious mental illness and among the homeless population, one in four lives with serious mental illness.

Substance use disorders often develop as a way to cope with or mask symptoms of mental illness, Windecker said.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, substance use disorder (SUD) accompanies other mental illnesses about 25% of the time. And those who receive treatment for over-the-counter opioids are diagnosed with or show symptoms of mental illness 43% of the time.

“You can’t treat substance use disorders without treating mental health,” Windecker said.

Legislationnot

Windecker, in partnership with the Department of Health and Human Services, plans to propose a new model that would place mental health and addiction treatment on the same level of reimbursement as physical health for the first time.

The model, called Certified Community Behavioral Health Centers (CCBHC), would also be accessible in rural and border communities.

“We reviewed many aspects of the model to ensure it would meet the state’s rural and frontier needs and replace community services that were decimated by the 2017/2018 budget cuts,” Windecker said.

It will also be imperative that the 2023 Legislature adopt the recommendations of the Governor’s Supplier Rate Study, Windecker said.

The rate study found that most programs needed a 10 to 25 percent increase in Medicaid rates to remain viable. The total cost to the state to cover the cost of these services is $32 million.

“Without these safety net providers, the mental health and addiction treatment system will collapse,” Windecker said. “With a $1.7 billion revenue surplus and a recreational marijuana tax available, this is a small amount to spend fixing a system that has long been underfunded and running at a loss. “

Aldwyn Boscawen, founder of Morale (moraleapp.co), offered some tips for tackling tough topics.

Comments are closed.